|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education

Incentives

|

All parents want the best for their

children. To help their offspring

achieve a bright future, wise parents

will start planning early to provide

them with the best possible higher

education. In support of this effort,

the Economic Growth and Tax Relief

Reconciliation Act of 2001 (the

Tax Relief Act) provides a variety

of tax incentives and tax breaks

for higher education. As with all

aspects of this legislation, these

changes are complex, phase-in or

out according to varying schedules,

and are scheduled to "sunset on

December 31, 2010, unless Congress

takes action in the interim.

|

|

The extensive list of changes

includes important modifications to education

IRAs, now known as Coverdell Education

Savings Accounts (Coverdell ESAs), and

qualified tuition programs, as well as

to the tax treatment of student loan interest,

employer-provided educational assistance,

and other higher education-related expenses.

A more detailed summary of each follows.

Coverdell ESAs

The annual contribution limit to a Coverdell

ESA has been raised from $500 to a more

substantial $2,000. Taxpayers no longer

face an excise tax on contributions to

a Coverdell ESA when made in the same

year as contribution to a qualified tuition

program on behalf of the same beneficiary.

And, taxpayers may claim a Hope Scholarship

Credit or Lifetime Learning Credit

for any taxable year and still exclude

distributions from a Coverdell ESA for

the same student from their gross income,

as long as they do not apply to the same

educational expenses.

The changes affecting Coverdell ESAs are

remarkable in that the Tax Relief Act

now allows qualified expenditures from

such accounts to pay for elementary and

secondary school tuition and associated

costs. Covered expenses can include room

and board, computer equipment, tutoring,

uniforms, and extended day program costs.

Contributions for any tax year after 2001

are now permissable until April 15th of

the following year, instead of December

31st. In addition, contributions to Coverdell

ESAs may be received from corporations,

tax exempt organizations, and other entities.

The new law also allows contributions

that benefit a special needs student to

continue after the beneficiary reaches

18 years of age. All Coverdell ESA provisions

became effective in January, 2002.

Qualified Tuition Programs

Prior to the Tax Relief Act, individuals

could only pre-pay higher education tuition

costs under state-sponsored qualified

tuition programs. Now, eligible private

higher education institutions may sponsor

certain programs (as long as such funds

are held in trust). Distributions from

qualified tuition programs are excludable

from gross income as long as they are

used to pay for qualified expenses (for

existing state-sponsored programs and

beginning in 2004 for newly established

private programs). Additionally, taxpayers

may concurrently claim a Hope Scholarship

or Lifetime Learning credit under the

same rules applying to Coverdell ESAs

described above.

The penalty tax on distributions not used

for qualified expenses has been modified,

and the definition of qualified expenses

for special needs beneficiaries has been

expanded. The Tax Relief Act also allows

rollover treatment for a single transfer

per beneficiary between qualified tuition

programs in any 12-month period. These

new education incentives are generally

effective for taxable years beginning

in 2002, with the exception of the exclusion

from gross income provision for distributions

from private programs noted above.

Temporary Deductibility of Higher Education

Expenses

An above-the-line deduction is temporarily

established for qualified higher education

expenses (as defined under the Hope Scholarship

credit). For 2002 and 2003, single taxpayers

with adjusted gross income (AGI) not

exceeding $65,000 are entitled to a maximum

deduction of $3,000 each year. For 2004

and 2005, single taxpayers with AGI not

exceeding $65,000 may deduct up to $4,000

each year, while those with AGI from $65,000-$80,000

may deduct up to $2,000 each year. Married

taxpayers filing jointly face AGI limits

twice those of single taxpayers. This

deductibility provision expires in 2006.

Student Loan Interest Deduction

As of 2002, the Tax Relief Act completely

repealed the limitation that payments

be attributable to the first 60 months

in which they are required. In addition,

eligibility for the deduction phases out

between AGI of $50,000-$65,000 for single

taxpayers (up from $40,000-$50,000) and

between AGI of $100,000-$130,000 for married

taxpayers filing jointly (up from $60,000-$75,000).

Employer-Provided Educational Assistance

Exclusion

The $5,000 annual exclusion for employer-provided

educational assistance has been permanently

extended for courses begun after December

31, 2001 and it now applies to both undergraduate

and graduate education.

Stay Current

In addition to the major changes noted

above, the Tax Relief Act also contains

provisions that affect the taxable status

of certain scholarship awards and that

modify the tax benefits associated with

certain bonds issued for public school

educational facilities. Thus, staying

abreast of tax changes and education incentives

can help you best plan for your own, or

your child's education.

|

|

|

|

Kiddie

Credits

|

In today's world, where the cost

of living continues to rise, the

expense of raising a family is also

rising. Now for the good news. .

.among the many changes in the Economic

Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation

Act of 2001 (the Tax Relief Act),

some of the benefits are targeted

specifically toward families with

children. As with other provisions

in the legislation, the relief related

to child credits may be phased-in

over many years and will "sunset"

come 2011.

|

|

The Tax Relief Act both

increases and expands existing tax breaks

aimed at assisting parents: the child

tax credit; the adoption credit and exclusion;

and the dependent care tax credit. It

also establishes a new business tax credit

related to employer-provided child care.

Below are highlights of the major implications

for each.

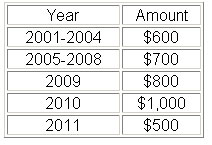

Child Tax Credit

The Tax Relief Act gradually doubles

the existing child tax credit to $1,000

per child over the ten-year life of the

legislation.

The existing adjusted

gross income (AGI) limits for eligibility

are left unchanged at $55,000 for single

taxpayers and $110,000 for married taxpayers

filing jointly. The new law allows the

credit to be refundable up to a specified

percentage of the taxpayer's earned

income in excess of $10,000 (indexed

annually for inflation), initially 10%

from 2001-2004 and 15% thereafter.

The Tax Relief Act also repeals the

alternative minimum tax (AMT) offset

of refundable credits and permanently

allows the child tax credit to be claimed

against the AMT. The present-law rule,

allowing families with three or more

children to receive a refundable credit

up to the amount by which the taxpayer's

Social Security taxes exceed their earned

income credit, remains applicable to

the extent such amount is greater than

their refundable credit under the new

law. In addition, the new law clarifies

that the refundable portion of a credit

shall not constitute income and shall

not be considered when determining eligibility

or calculating benefits under any federal

program or any state or local program

receiving federal funds.

Adoption Credit and Exclusion

The Tax Relief Act permanently increases

the adoption credit to $10,000 per eligible

child and permanently allows the credit

against the AMT. In addition, up to $10,000

per eligible child in employer-provided

adoption assistance may now be excluded

from income. Beginning in 2003, a taxpayer

finalizing a special needs adoption need

not have qualifying expenses to be eligible

for the credit or exclusion. The income

phase-out range for both the credit and

exclusion is doubled to $150,000 of modified

AGI. All provisions became effective in

2002 unless otherwise noted.

Dependent Care Tax Credit

The new law increases to 35% (from 30%)

the rate at which qualifying expenses

may be eligible for the dependent care

tax credit. It also increases the amount

of employment-related expenses that are

eligible for the credit to $3,000 per

qualifying individual (from $2,400) and

to $6,000 for two or more qualifying individuals

(from $4,800). The beginning of the income

phase-out range is increased to $15,000

of AGI. All provisions relating to the

dependent care tax credit became effective

in 2002.

Credit for Employer-Provided Child

Care

The Tax Relief Act allows employers to

claim a tax credit for up to 25% of qualifying

expenses for employee child care and up

to 10% of qualifying expenses for child

care resource and referral services, up

to a maximum credit of $150,000 per year.

All for the Children

With these targeted changes, the Tax Relief

Act aims to direct a portion of its benefits

to providing a helping hand to growing

families. Therefore, whether you're already

a parent of minor children or considering

expanding your family in the near future,

you may want to consult with a qualified

professional to help ensure you are able

to take full advantage of these more generous

tax breaks.

|

|

|

|

Marriage

Penalty Relief

Over the years, the tax

system has often thrown a few "clouds"

over the institution of marriage. However,

there is now some good news for married

couples. The Economic Growth and Tax

Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (the

Tax Relief Act) includes partial relief

for married taxpayers from the additional

"penalties" that can be imposed upon them.

The changes only eliminate the so-called

marriage penalty in certain circumstances-such

as related to the standard deduction,

the lower-income rate brackets, and the

earned income credit-while leaving it

unchanged in others. The targeted relief

is designed to benefit lower-income taxpayers

the most, is gradually phased in over

the next decade, and will "sunset" on

December 31, 2010 along with all other

provisions in the legislation.

Among the many worthy reforms, the new

legislation: expands the number and types

of plans available; increases the amounts

that may be contributed to such plans;

enhances portability; accelerates vesting;

and strengthens participant protections.

Below are highlights of the major changes

included in the bill.

Standard Deduction Parity

Specifically, the Tax Relief Act will

increase the standard deduction

for a married couple filing jointly over

a five-year phase-in period to twice the

standard deduction for a single taxpayer.

Beginning in 2005, the standard deduction

for joint filers will be set at 174% of

the deduction for singles, then 184% in

2006, 187% in 2007, 190% in 2008, and

finally 200% in 2009 and thereafter. As

most taxpayers with higher incomes tend

not to take the standard deduction, they

will continue to be subject to the marriage

penalty despite this change.

Partial Rate Bracket

Adjustments

Lower-income taxpayers will be pleased

to note that the new 10% income tax rate

bracket created under the new law establishes

an upper limit for married taxpayers filing

jointly that is twice that for single

taxpayers from its inception in 2002 and

thereafter. Additionally, the 15% rate

bracket for joint filers will be steadily

increased over a four-year phase-in period

beginning in 2005 to twice that of the

corresponding rate bracket for singles.

As such, the upper limit of the 15% bracket

for joint filers will be set at 180% of

the end point of the 15% bracket for singles

in 2005, then 187% in 2006, 193% in 2007,

and finally 200% in 2008 and thereafter.

For higher-income taxpayers, the remaining

four rate brackets will continue to be

subject to a marriage penalty built into

their structure that is not addressed

by the provisions of the bill.

Earned Income Credit

The Tax Relief Act also increases both

the lower and upper limits of the earned

income credit phase-out range by $1,000

for 2002-2004, by $2,000 for 2005-2007,

and by $3,000 for 2008 and adjusted for

inflation thereafter. In addition, the

definition of a child for purposes of

the credit is simplified, the present

law tie-breaking rules are modified, and

special rules are implemented pertaining

to cases involving child support. The

definition of earned income for purposes

of the credit is also modified to exclude

nontaxable employee compensation, and

the calculation of the credit is partly

simplified.

Saying "I do" Becomes Slightly Less Taxing

While most people do not base marital

decisions primarily on issues of taxation,

it's nice to see the new law address some

of the inequities imposed on married taxpayers

built into the Internal Revenue Code (the

Code). In particular, lower-income couples

(frequently younger couples just starting

out) will see the most relief under these

new provisions designed to alleviate,

at least in part, the marriage penalty.

|

|

|

|

Pension

Reform

|

When it comes to the subject of

taxes, many people may just want

to "hit the snooze button." However,

when it comes to the subject of

taxation and retirement planning,

there is some interesting news worth

heeding. The Economic Growth and

Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of

2001 (the Tax Relief Act) included

numerous, substantive changes to

the rules governing retirement and

pension plans. Much like the rest

of the law, these sweeping provisions

can be quite complicated, are phased-in

or phased-out according to various

timetables over the next decade

and ultimately face "sunset" in

2011, unless Congress takes action

in the interim.

|

|

Among the many worthy reforms,

the legislation: expanded the number and

types of plans available; increases the

amounts that may be contributed to such

plans; enhanced portability; accelerated

vesting; and strengthened participant

protections. Below are some highlights

of the major changes included in the bill.

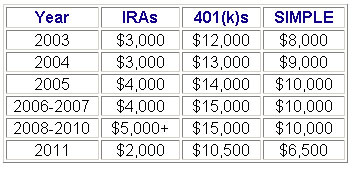

Annual contribution limits to Individual

Retirement Accounts (IRAs) (both traditional

and Roth IRAs) will gradually increase

to $5,000 in 2008 (adjusted for inflation

thereafter). Annual elective deferral

limits for 401(k)-type plans (including

403(b) annuities and salary

reduction SEPs) will steadily rise

to $15,000 in 2006 and thereafter. The

annual elective deferral limit for a SIMPLE

plan will rise gradually to $10,000

in 2005 and thereafter. A schedule of

these limits follows:

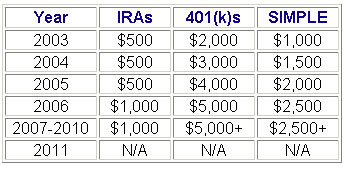

"Catch-Up" Contributions and Elective

Deferrals

In recognition that older taxpayers may

not have as long to benefit from the increased

contribution limits, the new law permits

those age 50 and above (who fall within

the standard adjusted gross income

(AGI) limits for regular contributions)

to make additional "catch-up" contributions

to their IRAs up to a maximum of $1,000

in 2006 and thereafter. "Catch-up" elective

deferrals are also permitted to 401(k)-type

plans (up to $5,000 in 2006 and adjusted

for inflation thereafter) and to SIMPLE

plans (up to $2,500 by 2006 and adjusted

for inflation thereafter). In addition

to these dollar limits, combined annual

elective deferrals and "catch-ups" may

not exceed the participant's annual compensation.

A schedule of "catch-ups" follows:

Qualified Plan Limits

The compensation limit that may be taken

into account under qualified plans in

applying nondiscrimination rules and in

determining allocations or benefit accruals

remains at $200,000 in 2003 (indexed for

inflation in $5,000 increments). The annual

limit on additions to a defined contribution

plan will remain at $40,000 in 2003 (indexed

for inflation in $1,000 increments). For

2003, the annual benefit limit under a

defined benefit plan increases

to $160,000 subject to adjustment for

inflation.

Roth 401(k) and 403(b)

Accounts Beginning in 2006, the Tax Relief

Act allows 401(k) and 403(b) plans to

incorporate a "qualified Roth contribution

program" into their plan. Participants

in these programs will be able to designate

all or a portion of their elective deferrals

as after-tax Roth contributions, with

qualified distributions not subject to

income taxes upon withdrawal (although

qualified distributions are not subject

to income taxes upon withdrawal, there

is a 10% federal income tax penalty on

certain withdrawals taken before age 59

½).

Tax Credit for Contributions

Lower-income workers will now be able

to claim a tax credit, instead of merely

a tax deduction, for their contributions

to qualified retirement savings plans.

Married taxpayers filing jointly earning

less than $30,000 will be entitled to

a maximum 50% credit.

Accelerated Vesting Schedules

The Tax Relief Act established two accelerated

vesting schedules that apply to employer

matching contributions. Plans will

now have to provide participants with

either full vesting after three years

of service or 20% vesting each year beginning

in the second year of service, resulting

in full vesting in the sixth year.

Increased Portability

The Tax Relief Act enhanced portability

of pension assets by allowing rollover

distributions from qualified plans, 403(b)

annuities, and 457 plans into any other

such plan, including rollovers of after-tax

contributions. Additionally, the Internal

Revenue Service (IRS) has the authority

to grant hardship waivers of the 60-day

rollover restriction.

Enhanced Participant Protections In response

to the controversy surrounding conversions

of traditional defined benefit plans into

cash balance plans that can potentially

reduce future benefit accruals for certain

participants in such plans (particularly

older workers), the law expanded the notice

requirements applicable to defined benefit

plan amendments. While previous law required

plan administrators to provide written

notice to participants of certain plan

amendments, the Tax Relief Act modified

both the Internal Revenue Code (the Code)

and the Employee Retirement Income Security

Act (ERISA) to expand the circumstances

requiring notice to participants, while

clarifying that "sufficient information"

must be provided within a "reasonable

time" prior to any amendment's effective

date.

SeekGuidance

By offering something for nearly everyone,

the Tax Relief Act provides a much-deserved

opportunity to increase your retirement

savings and security on a tax-deferred

basis. It also presents a significant

planning challenge due to its considerable

complexity. As such, it may be prudent

to seek out the guidance of qualified

professionals to assist you in revising

and updating your retirement savings program

to make the most of these promising reforms.

|

|

|

|

Real

Estate Exchanges—A “Capital Gain”?

|

With the passage of the Taxpayer

Relief Act of 1997, homeowners who

own appreciated residential property

are given a major capital gains

tax break. Those individuals who

own investment or corporate real

estate are not afforded the same

"luxury." Although their options

are limited, a like-kind exchange

may be an appropriate tax planning

mechanism for deferring capital

gains taxes.

|

|

Exchanging Basics

A "like-kind" exchange is a popular method

of deferring taxation upon the disposition

of a piece of property. In a like-kind

exchange, property held as an investment

or for productive use in a trade or business

is exchanged for another piece of property

of the same nature or character (but not

necessarily of an equivalent grade or

quality).

The exchange must consist of tangible

property, such as real estate. Securities,

evidences of indebtedness, and partnership

interests are not eligible for like-kind

exchange treatment. Exchanging properties

that are of a different kind or class

do not qualify as a tax-deferred like-kind

exchange.

In its simplest form, the transaction

might take the form of a simultaneous

exchange by "A" of a piece of rental property

for a similar piece of rental property

owned by "B." Sometimes, however, "B"

will be interested in acquiring "A`s"

property, but owns no property in which

"A" is interested. In this situation,

the parties can effect a delayed exchange.

For example "A" can transfer property

to "B" and direct "B" to purchase another

property that "A" would like to own. "B"

purchases that property and transfers

it to "A" in exchange for the property

"A" transferred to "B."

In order to qualify as a

like-kind exchange (under Code Sec. 1031),

the transaction must meet the following

requirements:

- The property

to be received by "A" in the exchange

must be identified within 45 days following

the transfer of the property from "A"

to "B" in the exchange, and,

- The like-kind

property must be received by "A" within180

days after the date of transfer or,

if earlier, before the due date for

filing "A`s" federal income tax return

for the tax year (including extensions).

Professional Assistance

a Must

For all exchanges, a qualified intermediary

(someone who is not deemed to be an agent

of one of the parties-- i.e., accountant,

attorney, or real estate broker) may be

necessary to ensure constructive receipt

of funds (which might trigger recognition

as a taxable sale) has been avoided.

If only like-kind property is received

in an exchange, no taxable gain or loss

will be reported for federal income tax

purposes as a result of the exchange,

regardless of the tax basis in (and value

of) the respective properties.However,

if in addition to like-kind property,

cash or other property is received that

is different in kind or class from the

property transferred (in other words,

nonlike-kind property which is often referred

to as "boot"), any gain realized in the

exchange will be taxable to the extent

of the sum of the amount of cash and the

fair market value of the nonlike-kind

property received. Any loss realized in

such an exchange may not be taken into

account in calculating federal income

tax.

Like-kind exchanges can provide substantial

tax benefits beyond the tax deferral of

the immediate transaction. The deferral

could become permanent (for income tax

purposes) if the property were to be held

until death, at which time its basis would

be "stepped up" to its fair market value

(FMV). However, holding such highly appreciated

property in one`s estate could have adverse

estate tax implications.

Before You Jump Ahead.

. .

The more complex the transaction, the

greater the need to ensure it will pass

the scrutiny of the Internal Revenue Service.

Moreover, Congress occasionally considers

proposals to make it more difficult to

qualify nonsimultaneous exchanges involving

multiple parties. Consequently, prior

to considering any exchange, transferors

should examine all details of the transaction

to see if it can be made according to

the current rules for a like-kind exchange.

|

|

|

|

Some

Helpful Information on Income Tax Filing

|

With April 15th fast approaching,

it is time to get down to business

and prepare your income tax return.

By now you have probably received

your W-2 Form(s) from your employer

and various 1099 Forms from your

bank or investment accounts. You

should have also received your 1040

package from the Internal Revenue

Service (IRS). If you haven’t, your

local post office has all the forms

you need. Take a moment to review

the following tax filing options

and issues, and get one step closer

to completing your taxes.

|

|

Electronic Filing.

The IRS has implemented several new filing

methods and forms for computers. Currently,

individuals filing a short form who have

access to a computer (and the appropriate

software) can file their return electronically

using a modem. By the year 2007, the IRS

hopes to make electronic filing available

for taxpayers with more complex returns.

Using Your Computer.

Numerous tax planning computer software

programs that can help take some of the

mystery and mathematical headaches out

of income tax return preparation are available.

These easy-to-use, menu-driven programs

prompt you to input tax information directly

from your tax forms and records. When

you are through, the program will print

out Form 1040-C. This printout should

be signed and mailed (together with the

appropriate tax forms, etc.) for filing

with the IRS.

Late Filers.

Individuals with complex tax planning

issues may need additional time to compile

their data. If you can’t complete your

tax return by April 15th, you can probably

get an automatic extension of four months

for filing a return (but not for payment

of tax) provided that Form 4868 is properly

filed and accompanied by payment of estimated

tax owed for the year. No late payment

penalty will be imposed if:

- the tax

paid with Form 4868 is at least 90%

of the total tax due with Form 1040

and,

- the remaining

unpaid balance is paid with the completed

return within the extension period.However,

if the amount of tax included with the

extension request is insufficient to

cover the taxpayer`s liability, interest

will be charged on the overdue amount,

including other penalties.

If you expect to owe taxes and are concerned

that you may be unable to make a full

payment to the IRS by April 15th, it is

important that you make at least a partial

payment when it comes time to file your

tax return. Include a letter explaining

your situation and then immediately contact

your local IRS office. In future years,

keep in mind that filing early results

in quicker refunds from the IRS and tends

to eliminate the frustrations typically

experienced by late filers (e.g., obtaining

answers to last-minute questions, searching

for additional forms, etc.).

Maintaining Your Tax Records.

Generally, the IRS has up to three years

to conduct an audit, either randomly or

based on a questionable return. However,

if income is misstated by 25 percent or

more, the IRS has up to six years to enact

an audit (there is no limitation if the

IRS suspects fraud). Thus, it is generally

wise to hold on to tax records (tax returns,

W-2s, other forms, etc.,) for six years.

Questions for the IRS.

The IRS has all refund information on

computer and you can find out the current

status of your refund by calling the

IRS Tele-Tax service line. The Tele-Tax

service also has recorded answers to frequently

asked questions that can help make tax

preparation a whole lot easier. In order

to find out the toll-free number for your

area, dial the national toll-free service

directory (800-555-1212). In addition,

if you are using the Internet, the IRS

Website is filled with helpful information

and tips. You can visit them at http://www.irs.gov

Seeking Professional Assistance.

One question commonly asked by many taxpayers

is whether to prepare one`s own return

or seek out a tax return preparer. Some

taxpayers are uncomfortable preparing

their own returns because of complex schedules

(e.g., Schedule C for the self-employed

business expenses), or tax issues (e.g.,

capital losses carried over from a previous

tax year, complicated deductions, etc.).

If you fall into this category, you may

wish to save yourself needless worry and

consult with a qualified tax professional.

|

Taking the time now to prepare

and file your return will certainly

help make this tax season less stressful

and much more relaxing.

|

|

|

|

|

Sunrise

Sunset

|

Passage of the new tax law, the

Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation

Act of 2001 (the Tax Relief Act),

has created new planning opportunities

for many taxpayers. However, each

individual and family may be affected

quite differently depending on their

particular goals, circumstances,

and time horizon. In addition, the

Tax Relief Act will automatically

expire on December 31, 2010 and

revert to prior law unless Congress

takes action to retain all or specific

aspects of its provisions.

|

|

Sweeping Scope and Complexity

In total, the legislation is estimated

to result in nearly $1.35 trillion in

tax cuts over the next ten years, representing

the largest tax cut since the 1981 rate

reductions under President Reagan. While

the scope of the changes included in the

final language of the bill is far-reaching,

a comparable degree of complexity accompanies

this relief, largely due to somewhat arbitrary

budgetary constraints. In particular,

most of the benefits contained in the

bill are phased-in or phased-out to varying

degrees over multiple years during the

course of the next decade.

Despite the delayed nature of most benefits,

and the targeted nature of certain provisions,

the new law succeeds in providing meaningful

tax relief for nearly all taxpayers, through

one or more of the following major categories

of changes.

|

|

Income Tax Cuts.

The Tax Relief Act carves a new

10% income tax rate bracket out

of the existing 15% rate bracket

and also provides for marginal cuts

in the higher-income rate brackets

|

|

|

Modified Transfer Taxes.

The Tax Relief Act contains substantial

changes to the taxation of asset

transfers, including a gradual phase-out

and repeal of the estate tax and

generation-skipping transfer tax,

while leaving gift taxes in force

and placing new income tax consequences

on post-mortem transfers

|

|

|

Significant Pension Reform.

Look for numerous and sweeping changes

to pension plans and IRAs, including

expanding the number and types of

plans available, increasing the

amounts that may be contributed

to such plans, enhancing portability,

accelerating vesting, and strengthening

participant protections.

|

|

|

Marriage Penalty Relief.

The Tax Relief Act provides partial

relief from the so-called marriage

penalty, targeted primarily to lower-income

taxpayers.

|

|

|

Enhanced Education Incentives.

There are several provisions designed

to enhance education incentives,

including important changes to education

IRAs, and qualified tuition programs,

as well as the tax treatment of

higher education expenses, student

loan interest, and employer-provided

educational assistance.

|

|

|

Expanded Kiddie Credits.

Targeted relief for growing families

is also on the way, including a

doubling of the child tax credit,

as well as increases to the adoption

credit and exclusion, the dependent

care tax credit, and the credit

for employer-provided child care.

|

Miscellaneous Provisions

In addition to the changes within each

of these broad categories, the Tax Relief

Act also contains several minor miscellaneous

provisions, including: delaying the due

date for two specific corporate estimated

tax payments (effectively pushing the

revenue into the federal government's

next fiscal year); temporarily increasing

the alternative minimum tax (AMT) exemption

amount; granting authority to the Treasury

to postpone certain tax-related deadlines

for taxpayers affected by a presidentially-declared

disaster; and extending favorable tax

treatment to certain restitution payments

to Holocaust victims.

One "Sunset" We Hope not to See

As part of the final compromise worked

out in Congress by the conference committee,

the entire legislation is ultimately subject

to an obscure, budgetary "sunset" provision

mandating that all provisions contained

in the bill expire after December 31,

2010 (absent additional action by Congress

in the interim). As such, all changes

implemented over the next ten years will

be automatically repealed after 2010,

reverting in 2011 to their status prior

to the Tax Relief Act's enactment.

Educate Yourself and Seek Assistance

When carefully scrutinized, the Tax Relief

Act reveals a complex structure involving

numerous benefits with varying effective

dates. Of course, the time-delayed aspects

of that relief will ultimately determine

how valuable the Tax Relief Act turns

out to be for each taxpayer and household.

As such, the challenge now becomes sorting

out the various provisions through self-education,

which you may begin by examining the remaining

sections of this booklet, each of which

provides a more detailed explanation of

one of the major categories listed above.

Then, once you have familiarized yourself

sufficiently with the highlights of the

new law, you will want to consult with

your qualified professional(s) to determine

precisely how these numerous, and sometimes

conflicting, benefits will affect your

individual financial circumstances and

future planning decisions.

|

|

|

|

Tax

Basics: Understanding Tax Basis

You probably know that when a capital

asset is sold for profit, it is subject

to a capital gains tax. But, did you

know that how you acquired the property,

and what you have done with it since

acquisition, will affect the determination

of basis and, ultimately, the gain on

which the tax is paid?

Basis is used to determine

gain upon the disposition of any asset.

In simple terms, basis is an owner's

out-of-pocket cost for the asset. For

purchased property, the starting basis

is the original price paid (plus any

acquisition costs). An asset's basis

can be increased (e.g., by making improvements

to real property) or decreased (e.g.,

after a casualty loss reduces the value

of an asset), and can change according

to how it was acquired and the nature

of the eventual disposition. Adjusted

basis refers to changes in basis after

an asset was acquired.

Here's a closer look at basis and how

it can affect capital gains:

Selling an Asset

Assume Helen Bradley (a hypothetical

case) bought an antique dining room

set for $25,000. While having the antique

appraised, Helen learned its current

fair market value (FMV) is $85,000.

Helen’s basis is the original cost of

$25,000. If she were to sell the antique

dining room set at current FMV, her

taxable gain would be $60,000 ($85,000

selling price minus $25,000 basis).

"Gifting" an Asset

Now, suppose Helen decides not to sell

the antique set, but rather to give

it to her daughter Laurie. As a general

rule, the donee (Laurie) assumes

the basis of the donor (Helen) at the

time of the gift (plus a portion of

any gift tax incurred by the transfer).

However, if Laurie were to sell the

antique dining room set, her gain or

loss on the sale would depend upon whether

the FMV of the antique at the time of

the gift was greater, or less, than

the adjusted basis at the time of the

gift.

If the FMV at the time of the gift is

greater than the donor's (Helen) basis,

then Helen’s basis is used to determine

gain or loss (in this case, $25,000).

However, suppose the FMV at the time

of the gift is less than Helen’s basis—say

$15,000. In that case, the foundation

for determining a gain and loss are

different. For a loss, the donee's (Laurie's)

basis is the lesser of the donor's (Helen's)

cost of $25,000 or the FMV at the time

of the gift, which is $15,000. For a

gain assuming the antique is still valued

at $85,000 when Laurie sells it, the

basis remains Helen’s basis of $25,000.

Bequeathing an Asset

After reviewing these

rules with her accountant, and being

apprised of possible gift tax complications

for any gift exceeding $11,000 per person

per year (for the year 2004), Helen

wonders if other techniques exist to

transfer the antique dining room set

to Laurie with fewer tax complications.

Upon further investigation, Helen learns

that the basis of property acquired

by inheritance is adjusted to

the FMV of the property at the time

of the owner's death. Thus, if she were

to bequeath the antique to Laurie, Laurie's

basis in the antique would be the FMV

of the antique on the date of Helen's

death.

In summary, the main advantage of acquiring

property through inheritance is that

it allows the recipient to sell the

property shortly after inheriting the

property with little or no capital gains

tax. Assuming that an immediate sale

of an inherited asset would be at the

asset's FMV, there would be no recognized

gain since the basis (FMV) would also

be the same. Even if the asset were

held for some time after inheritance,

an eventual sale would result in smaller

capital gains tax, due to the higher

(stepped-up) basis established at inheritance.

Capital gains tax laws

can be complex. Understanding how

basis is determined can help you make

wise choices about disposing of your

capital assets. This knowledge can help

you minimize the tax burden for yourself,

your heirs, and those to whom you make

gifts.

|

|

|

|

The

AMT—Affecting More and More

|

It seems that nowadays, an increasing

number of middle class taxpayers

are being affected by the Alternative

Minimum Tax (AMT). This is rather

interesting, considering the AMT

was originally intended to prevent

taxpayers with substantial incomes

from avoiding tax liability through

the use of tax shelters.

|

|

On its most basic level,

the AMT is a minimum amount of income

tax that must be paid by each taxpayer.

The AMT is calculated under rules that

are, in many ways, quite different from

those used to calculate your ordinary

income tax liability. The AMT can serve

to increase your federal income taxes

if your federal income tax liability,

as calculated under AMT rules, is greater

than your ordinary federal income tax

liability as calculated without regard

to the AMT rules.

|

Congress implemented the AMT because

too many people were using tax shelters,

income tax deductions, and tax credits.

As a result, some individuals often

paid little or no income tax. So,

in recent years, Congress has continued

to modify the Alternative Minimum

Tax. Now, more than just the wealthy

are becoming affected. What does

that mean if you are in the middle

class?

|

Since significant modifications

were made to the AMT in 1986, there have

been changes in the economy. For instance,

healthcare costs have increased beyond

expectations; home equity buildup has

allowed homeowners to obtain substantial

equity loans; and state and local taxes,

in some cases, have remained at significant

levels. All these changes relate to the

AMT and to your income taxes. Consequently,

if you have tax deductions, tax-exempt

income, and tax credits, you may discover

that you are subject to the AMT.

Here’s a general overview

of some of the more common differences

between AMT rules and ordinary income

tax rules, that can increase a middle

class taxpayer’s chances of being subject

to the AMT:

- Medical

and dental expenses

that are greater than 10% of your adjusted

gross income (AGI) are deductible for

purposes of the AMT. However, medical

expenses are deductible for ordinary

income tax purposes to the extent they

exceed 7.5% of AGI. This difference

in tax treatment can make you more likely

to be subject to AMT if you have high

medical expenses for which you are taking

a deduction against your regular taxable

income.

- Taxes

you paid to

your state and local governments are

nondeductible for AMT purposes. However,

these items are deductible from your

regular taxable income. This includes

real estate, personal property, and

any other tax. Therefore, if you live

in New York, Massachusetts, California,

or a state with a significant income

tax, your chances of being affected

by the AMT are increased.

- Mortgage

interest you paid

and deducted may not be deductible for

the AMT even though it is generally

deductible from your regular taxable

income. If you obtained a home equity

loan that was not used to buy, build,

renovate, or improve your home, the

interest is nondeductible. Once again,

the likelihood that you could be subject

to AMT is increased.

- Employers

often use incentive stock options

as part of an employee’s compensation.

As an employee, you may have been given

a qualifying stock option to purchase

your company’s stock in the future.

Ordinarily, you would pay no income

tax at the time you receive the stock

option or at the time you convert the

option to the stock and receive a profit.

For ordinary tax purposes, tax is deferred

until the stock is sold. However, for

AMT purposes, the difference between

the fair market value (FMV) of

the stock and the amount paid for the

stock due to the option is generally

considered taxable income when the option

is exercised. This may make a big difference

for taxpayers with stock options, and

may significantly increase their chances

of being subject to AMT when they exercise

these options.

Many tax credits

and deductions are often not

used when calculating the AMT. In addition,

the standard deduction is also not considered.

If any of these areas resulted in a substantial

reduction of your ordinary income taxes,

you should consult with a qualified tax

professional to check your AMT status.

You may be able to take steps now to reduce

your exposure for the coming tax year.

|

|

|

|

Transfer

Taxes

|

To paraphrase a famous saying,

there are two things you can be

sure of in life-death and taxes.

When it comes to estate planning,

taxes will play an important role.

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief

Reconciliation Act of 2001 (the

Tax Relief Act), signed by the

president on June 7, 2001, contains

several statutory revisions related

to transfer taxation. Like most

other provisions in the Tax Relief

Act, the changes related to transfer

taxation are quite complicated,

are phased-in or phased-out over

various schedules during the ten-year

life of the legislation, and are

ultimately subject to the obscure,

budgetary "sunset" provision.

|

|

Transfer taxation broadly

addresses all forms of taxation related

to the transfer of assets between individuals

both during one's lifetime and at death,

including gift taxes, estate taxes, generation-skipping

transfer taxes, and income tax basis on

transferred assets. Below are highlights

of the major implications for each.

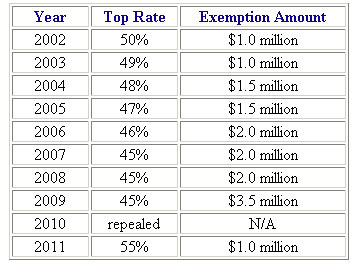

Estate Taxes

If the Tax Relief Act represents the final

word on the subject, it appears the infamous

"death tax" is going to die quite a slow

death. Specifically, the estate tax has

been repealed for precisely one year-2010-only

to be revived in 2011 due to the sunset

provision that applies to all aspects

of the bill. In the interim, the maximum

estate tax rate will be gradually reduced,

while the exemption amount per person

that can avoid any estate taxation will

be gradually increased, according to the

following schedule:

Generation-Skipping Transfer

Taxes

The generation-skipping transfer tax,

imposed on assets transferred to heirs

two or more generations removed from the

grantor, is also scheduled for repeal

in 2010. During phase-out, rates will

be pegged to the top estate tax rate throughout

the 10-year repeal period. The per person

lifetime exemption amount that can be

transferred without triggering generation-skipping

transfer taxes remains unchanged at $1

million.

Gift Taxes

While estate taxes may be headed for repeal,

gift taxes on lifetime transfers are here

to stay. The lifetime exemption amount

for gift tax purposes is increased to

$1 million in 2002 and remains constant

thereafter. The top gift tax rate mirrors

the top estate tax rate during the phase-out

period and is pegged to the top marginal

income tax rate (35%) beginning in 2010

and thereafter.

Income Tax Basis

No sooner will the estate tax be repealed

in 2010, when an arbitrary modified

carryover basis rule will take effect

that will potentially impose an income

tax liability on assets transferred from

a decedent at death. Prior to the Tax

Relief Act, appreciated assets transferred

at death received a "stepped-up" income

tax basis to fair market value (FMV) on

the date of death (or alternate valuation

date) for purposes of determining potential

capital gains tax liabilities upon the

subsequent sale of such assets. Now, post-death

transfers beginning in 2010 will retain,

or carry over, the basis from the decedent,

with two limited and restricted exemptions:

1) $1.3 million of tax basis will be allowed

to be added to certain assets; and 2)

$3 million of additional tax basis will

be recognized for assets transferred to

a surviving spouse.

Begin Planning Now

In addition to the major changes noted

above, the Tax Relief Act also contains

transfer tax-related provisions affecting

state death tax credits, conservation

easements, installment payment rules,

surtaxes, and certain recapture and refund

provisions. As such, whether you're just

beginning to establish an estate plan

or need to revisit and revise an existing

plan in the light of the new law, the

assistance of qualified professionals

is crucial to avoid pitfalls and ensure

your desired goals and objectives are

ultimately met.

|

|

|

|

What

Should You File—Joint or Separate Returns?

A common question for married people

is whether to file a joint return or to

file separately. Most married people tend

to file joint returns because the tax

rate is lower than that on separate returns.

However, here are some things to keep

in mind if you are considering filing

separately:

|

|

If spouses file separate returns

and one spouse itemizes deductions,

the other spouse must itemize also--even

if that spouse has zero itemized

deductions.

|

|

|

If separate returns are filed,

in most cases, neither spouse may

claim a credit for child and dependent

care or the earned income credit.

In addition, if the spouses lived

together at any time during the

tax year and file separate returns,

they may have to include up to one-half

of all Social Security benefits

received in their income.

|

|

|

If a taxpayer made contributions

to an Individual Retirement Arrangement

(IRA), the deduction is subject

to a phase-out rule if the taxpayer

and his or her spouse lived together

during the year and either one was

covered by an employee retirement

plan. Thus, the IRA limitations

cannot be expanded or avoided by

filing separate returns.

|

|

|

The $25,000 deduction for passive

activity losses resulting

from rental real estate ownership

is split when married individuals

file separately. Each spouse may

only deduct up to $12,500 of his

or her own passive rental real estate

losses for the tax year.

|

|

|

If spouses file separate returns,

each reports only his or her own

income, deductions, credits, and

exemptions. Exemptions may not be

split between married taxpayers.

For example, the parent who provides

the most monetary support for a

child (assuming all support for

the child comes from the two filing

parents), is the one entitled to

claim the dependent deduction. When

neither has provided more than one-half

of the dependent`s support, the

parents and other persons furnishing

support can, by written agreement

attached to their tax returns, allocate

the dependency exemption to one

specific person.

|

|

|

If a taxpayer files a separate

return, an exemption can be taken

for the spouse only if the spouse

has no gross income and was not

a dependent of another taxpayer.

|

|

|

If spouses file separate returns

for a tax year, they may amend those

returns and change to a joint return

at any time within three years of

the due date of the separate returns

(not counting extensions). If the

amount paid on the separate returns

is less than the total tax shown

on the joint return, the additional

tax due on the joint return must

be paid when filed. However, once

a joint return has been filed, the

taxpayers may not choose to file

separate returns for that year after

the due date for the return.

|

Your particular circumstances may make

filing separately more advantageous, but

you will need to "run the numbers" both

ways in order to make the proper determination.

|

|

|

|

Your

Income Taxes—Marginal Rates vs. Effective

Rates

Whether tax season has already passed

or is right around the corner, income

taxes are an issue you should remain familiar

with throughout the year. Here’s a quick

primer on the basics of taxation. There

are several definitions that are useful

in understanding the tax you actually

pay on your income. Gross income is

your total income from all sources, unless

specifically excluded by tax law (e.g.,

tax-exempt bond interest). Taxable

income is calculated by subtracting

all your allowable adjustments, deductions,

and exemptions from gross income. The

tax rates are then applied to taxable

income to determine how much tax is due.

There are two tax rates that are important

for understanding how your income is taxed.

The marginal tax rate is the rate applied

on your last dollar of earnings.

For the sake of illustration, let's assume

a purely imaginary tax system with two

rates: Income up to $10,000 is taxed at

5 percent and income in excess of $10,000

is taxed at 10 percent. If you earned

$15,000 in salary and received a $1,000

bonus, your marginal tax rate on the bonus

is 10 percent--that is, the rate on the

last dollar you received.

The effective tax rate, on the

other hand, is the overall rate at which

your income is taxed--it is calculated

by dividing total tax paid by total income.

Assume the same simple two-rate system

and an income of $15,000. The tax on the

first $10,000 in income is $500 ($10,000

x 5%). Since the rate is 10 percent on

income over $10,000, in this example $5,000

is taxed at 10 percent, generating another

$500 in tax ($5,000 x 10%). So, the total

tax comes to $1,000 ($500 plus $500).

Even though the top marginal tax rate

is 10 percent in this imaginary system,

the effective tax rate is only 6.7 percent

($1,000 total tax divided by $15,000 total

income).

What Do the Numbers Mean?

Your marginal tax rate will tell you the

rate that is applied to your last dollar

of taxable income. Unless you are on a

rate "bubble" (i.e., the point where two

rates meet), it will also tell you the

rate that would be applied to additional

taxable income. Furthermore, your marginal

rate will tell you the effective tax savings

of deductions. For example, a $1,000 deduction

for someone with a marginal tax rate of

28 percent gives an effective tax savings

of $280 ($1,000 x .28).

Your effective tax rate tells you the

percentage of your total income that is

paid in taxes. It is possible for a taxpayer

to have a high marginal tax rate with

a comparatively much lower effective tax

rate. Indeed, many income earners in the

highest marginal tax bracket are able

to substantially reduce their effective

tax rate by taking large tax deductions.

In reality, no one has a single "real"

tax rate. Both marginal and effective

tax rates are important numbers, providing

different pieces of tax information. When

used together, they can help you achieve

a better understanding of how the tax

system affects the money you earn. A qualified

tax professional can provide you with

additional information regarding your

particular situation

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|